fauntleroy tree walk

Douglas fir

lushootseed name:

latin name:

Pseudotsuga menziesii — Pseudotsuga is the Latin word for false hemlock, as this is not a true fir. True firs have upright cones, and the needles are not “friendly” to the touch.

family:

Family: Pinaceae, the pine family

Habitat

This species is found throughout the North American west but is most common from the Pacific Coast to the Cascade Crest. They prefer gravelly and well-drained soils of the higher regions of the ecosystem and are highly adaptable, living in moist riparian areas to the dry subalpine!

Identification

growth habit

Douglas fir is believed to be the tallest tree in the world, with one well-known tree that stood ~460 ft, a giant above the forest floor before it was cut down in the late 1800s. The tallest Douglas fir still in existence is ~320 ft, only 50 ft less than that of the tallest coastal redwood.

leaves

Rounded-tip needles that have a groove on the dorsal side. All needles are the same length. Notice how far the needles are from the ground; this is a mechanism to protect the trees canopy from burning in forest fires. If you look at the branch head-on, you’ll see it has a bottlebrush appearance, with needles being arranged around the stem.

flower

No flowers are present, as this is a coniferous species. This species has sharply pointed, glossy red buds that open up into small, papery and brown pollen cones in May–June.

fruits

Papery brown cone with 2-tailed bracts peeking out from underneath. There is a Coast Salish story that says that the Douglas fir allowed forest mice to climb up into its cones to escape forest fire years ago, leaving the cones to resemble mice hiding within the scales.

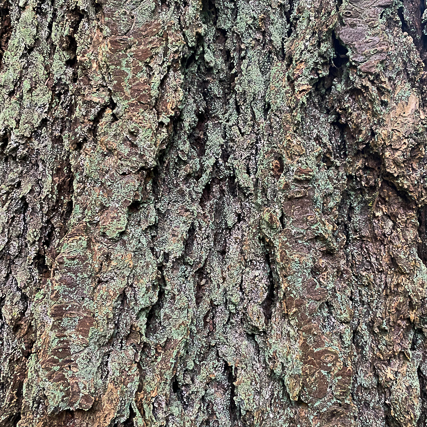

bark

Brown to gray and thick, deeply furrowed bark. This thick, platy bark protects the tree’s inner tissues from the dangers of forest fires.

look-a-likes

You might mistake this plant for the Western hemlock.

Western hemlock has an overall “drooping look,” while Douglas fir is more erect. Western hemlock needles are multiple different lengths, while Douglas fir needles are all the same length. Look for pearly white, rounded buds in the spring on Western hemlock and sharply, pointed red on Douglas fir. The easiest way to distinguish these trees is by looking at the cones. Douglas fir has larger, “mouse-tail” cones, while Western hemlocks have very small, flaky cones without tail-like bracts. Cones fall off in late summer, making the identification process more tricky.

Ecology

Douglas fir is the most common species in the Pacific Northwest! Due to years of evolutionary adaptation, this species has built resistance in form to forest fires with its thick bark and tall canopy far from the forest ground. This tall, clear canopy makes space for renewal as lower- dwelling and shade-tolerant plant species drop their seeds after natural or man-made disasters clear the area.

Furry and feathered friends alike — species like mice, voles, shrews, squirrels, pine siskin, sparrows, and dark-eyed juncos — relish the numerous seed-cones that this tree produces. Birds such as chickadees, nuthatches, and woodpeckers enjoy the grubs nestled under the bark, and cavity-dwelling species like flying squirrels enjoy the safety and warmth that this shelter creates. Butterflies, moths, deer, elk, pocket gophers, and more enjoy the tasty foliage as a food source.

Douglas fir has mast years, or years when it produces a crazy amount of seed-bearing cones. They do this to produce enough for both the animals that rely on the tree for food and to have enough left to sprout into more trees. They also have low-producing years, which controls rodent and bird population growth so that the seeds aren’t completely eaten. It’s all about balance in this forest ecosystem!

Ethnobotany

Douglas fir is a very fast-growing species and is the largest of that in the pine family. This has made it a staple for lumber and Christmas trees for years. Indigenous peoples of this land have used this plentiful wood to construct fishing tools, like harpoon shafts and dip-net poles.

The pitch, or resin, was also used as a water-tight caulking for canoes. The fresh spring needle growth was harvested in the spring and infused to extract vitamin C. Buds were chewed to treat sore throats and mouth sores. Pitch was also used as a salve to apply to wounds to speed up healing or to put on sore gums, and also as a sugar substitute.